What is Dupuytren's disease?

Dupuytren's disease is a benign condition which is more common in men. It derived its name from a French surgeon, Baron Dupuytren, who was one of the earliest surgeons to report the condition, which reputedly affected his coachman.

Causes of Dupuytren's disease:

The cause of Dupuytren's disease is unknown. Dupuytren's disease tends to be more common in some families, indicating that it may be a genetic predisposition to developing the condition. It is more common in people who smoke, drink excess alcohol, those who are diabetic, have liver disease or take treatment for epilepsy There is a geographical distribution to Dupuytren's disease, and it is much more common the further north you travel in Europe. The highest incidence of Dupuytren's disease is found in the Scandinavian countries. This has lead to it recently being referred to recently as the 'Viking disease'.

Symptoms of Dupuytren's disease:

Dupuytren's disease results in thickening of the layer of fascia (gristly tissue) that lies just beneath the skin in the palm of the hand and fingers. This may cause:

Nodules (lumps) in the palm of the hand or fingers

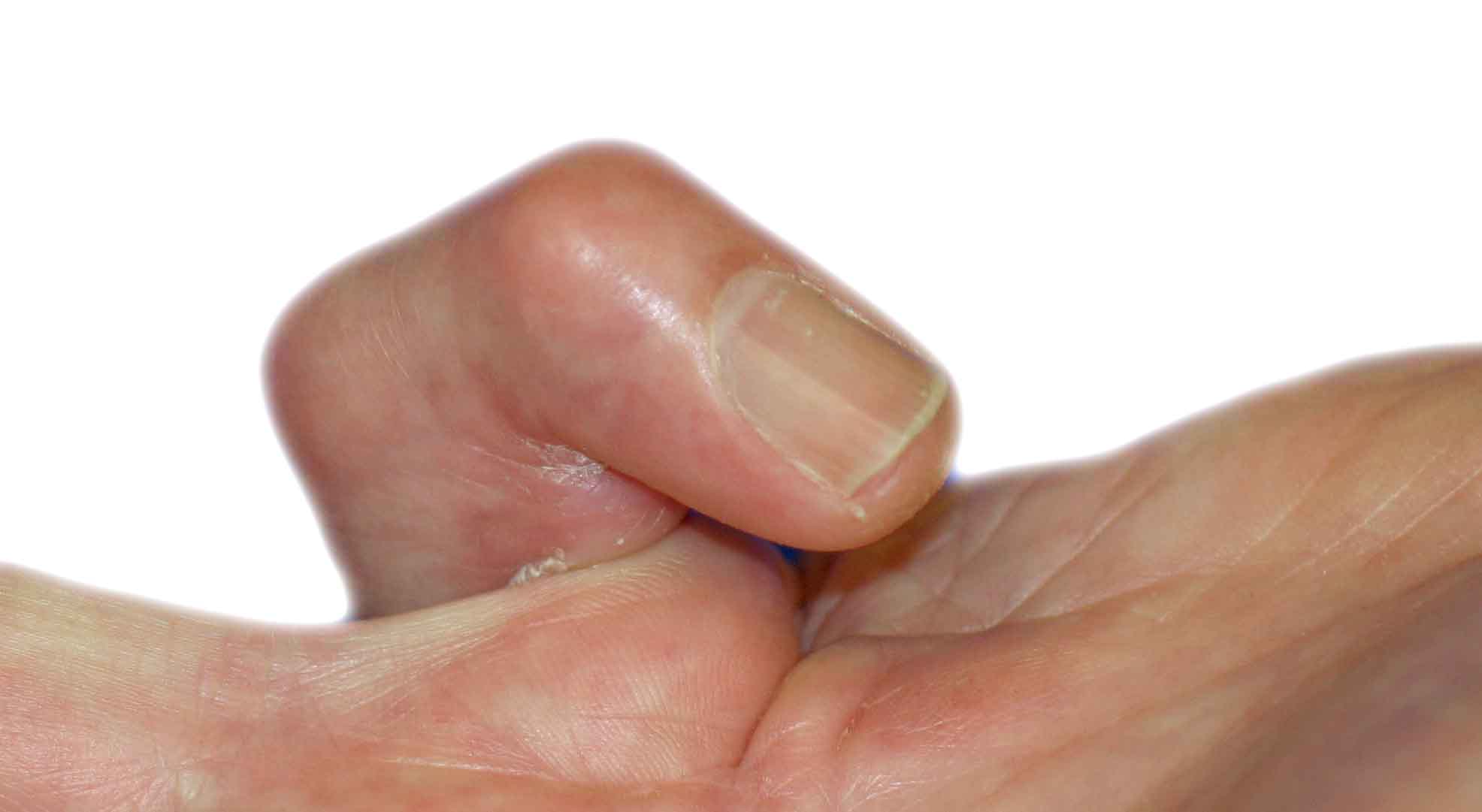

Figure 1: Dupuytrens disease of the little finger. Note the nodules in the skin and loss of finger extension

Pits in the skin. These are single or multiple and appear as small skin indentations

Figure 2: Pits in the palmar skin

Cords (tubes) of tissue which are longitudinal fibrous bands and they can affect one or more fingers. These cords pull the finger into the palm of the hand (figure 1) and it is not possible to actively or passively straighten the finger. The finger often gets in the way when wearing gloves, putting the hand into a trouser pocket or even poking their eye when washing the face. Flexion of the finger is normal and not affected. Dupuytren's disease is not usually painful, although in the early stages of the disease the nodules can be tender.

Figure 3: Dupuytrens disease causing a severe contracture of the little finger.

Nature of the disease:

-

the ring and little fingers are most commonly affected.

-

the disease may progress slowly, it may have periods of inactivity or it can progress rapidly

-

both hands are commonly affected

-

the skin is often infiltrated with the disease

-

involvement of the feet is seen is a small proportion. Other body parts may also be affected

-

recurrence is frequent

Treatment of Dupuytren's disease:

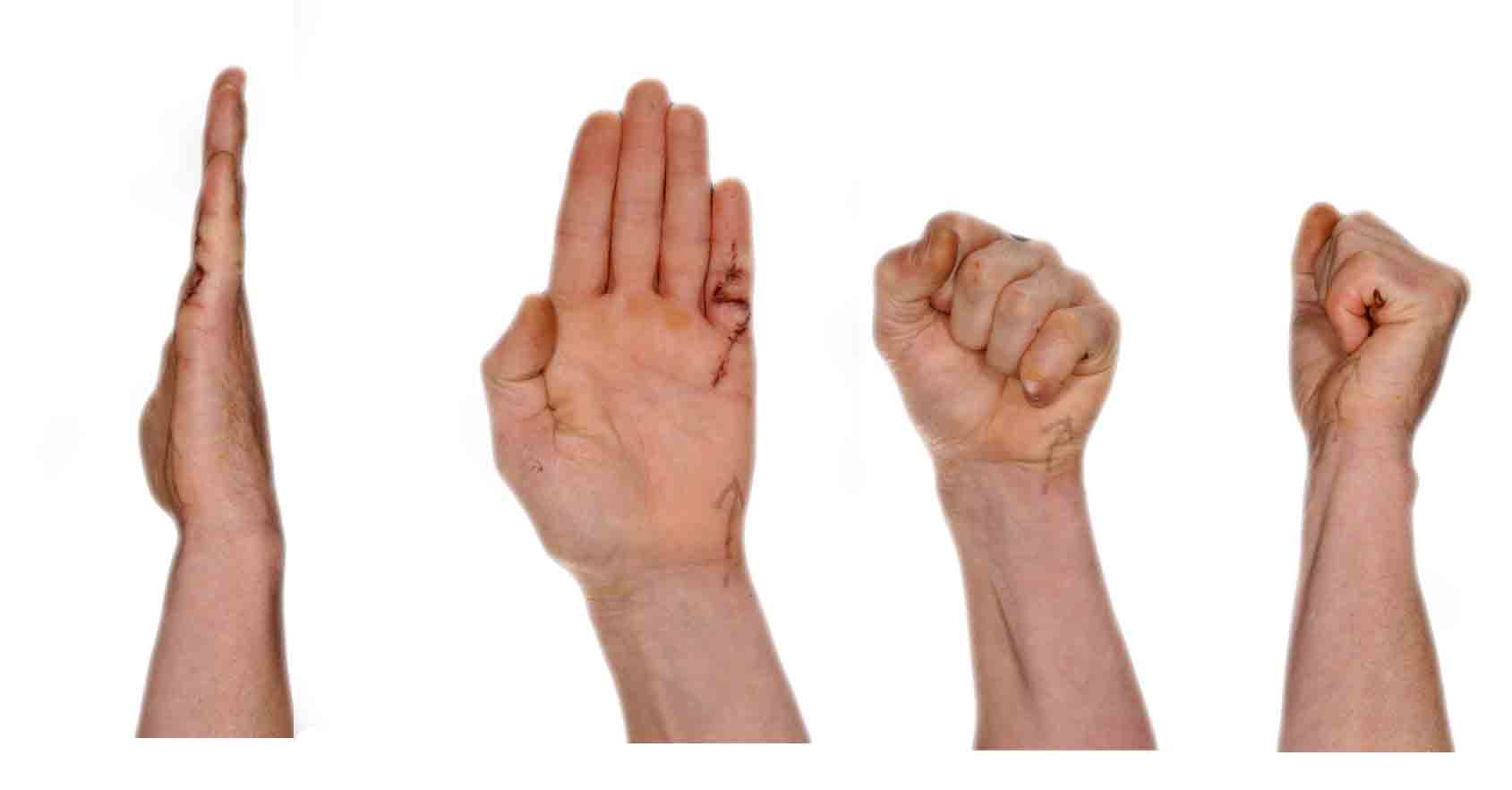

Despite ongoing research into the treatment of Dupuytren's disease, surgery remains the gold standard effective treatment. This usually removes the thickened Dupuytrens tissue, sometimes with the overlying skin. Surgery is usually considered necessary when there is greater than 30 loss of extension of the finger joints. Put more simply, this is when it is not possible to place the hand flat on a table top because the fingers are bent. Surgery usually removes the thickened tissue through z-shaped incisions, but sometimes the overlying skin is also removed and replaced with a skin graft. The surgery can be performed as a day-case procedure using either regional anaesthesia (putting the arm to sleep) or general anaesthesia. Postoperatively a bulky hand dressing remains for 2 weeks, following which the stitches are removed and the hand is mobilised. In some patients, postoperative physiotherapy may be necessary and others will have a custom made splint fitted to wear at night until the scar has become soft and mature.

More recently treatment is possible by injecting an enzymes (a collagenase) which softens the dupuytrens cord allowing it to be broken without surgery. This is relatively new treatment without long-term outcomes. It is not offered widely throughout the UK, although this may change once the results are known.

Complications and results of surgery:

Complications following surgery are recognised but infrequent.

-

wound infection (1%)

-

temporary scar tenderness

-

finger stiffness (avoided by early mobilisation)

-

nerve injury (resulting in permanently altered feeling in the finger)

-

bleeding

-

recurrence of the disease and contracture

-

arterial injury and loss of a finger (very uncommon)

It is not always possible to completely correct severe contractures of the finger joints (figure 2), even if all of the Dupuytren's tissue has been removed. This indicates that there have been changes to the joint itself and it is usually the consequence of a longstanding contracture. It is best to try and prevent this developing in the first instance.

Figure 4: Two weeks after surgery to remove Dupuytrens disease